Locating Anti-Racism in the ESL Curriculum

Back to Blog Locating Anti-Racism in the ESL Curriculum

Locating Anti-Racism in the ESL Curriculum

By Rob Sheppard

In this post, a follow-up to JPB Gerald’s post on this same blog, I discuss where ESL curriculum developers can integrate anti-racist work into an ESL curriculum.

A Preamble

Let me start with this: when asked to write a follow-up to Justin’s post on decentering Whiteness, I first thought, Me? Are you sure you should be asking cishet white male “native-speaking” me? It felt that white people writing about decentering whiteness could run the risk of inadvertently recentering whiteness. Upon further reflection, though, I remembered that white people are supposed to be shouldering the bulk of this weight of the anti-racist work, and this necessarily involves doing some writing and speaking. I reached out to Justin to get his thoughts on the matter and here’s what he said:

'If racialized people had the power to solve these problems alone, we wouldn't have these problems. This work will require white educators challenging whiteness alongside us. Just be thoughtful and open as you engage in your necessary pushback.'

I’ve still got a lot to figure out, but I hope I have something of value to contribute on the intersection of anti-racism and the topic most central to my work: ESL curriculum design.

Does Anti-Racism Belong in an ESL Curriculum?

I don’t think it’s unreasonable to ask in good faith whether anti-racism has a place in the ESL curriculum. In most contexts and programs, though, my answer to this question is an emphatic yes. Here are a few reasons why that is.

For one thing, racism is pervasive. In my fifteen years in the ESL classroom, I’ve seen racism, anti-Blackness, anti-Semitism, and Islamophobia (not to mention homophobia and transphobia) crop up more times and in more ugly forms than I care to count. The task of rooting out and eradicating racism requires a far-reaching, multi-front approach, one that certainly includes the classrooms where it continues to rear its head.

More specifically, though, the field of English language teaching is one uniquely rooted in colonialism, and thus bound up with various forms of racism in ways that go far deeper than “racism is everywhere.” If there is anywhere that whiteness is still shamelessly centered, it is in the field of English language teaching. Take a look at an ESL coursebook. Look at which Englishes are taught and assigned prestige. Look at which accents are upheld as “neutral” Examine what “professionalism” is code for. Incorporating anti-racism as a partial corrective into the ESL curriculum ranks among The Least We Can Do.

There are those among us who believe that simply by doing “good work” like ESL with pure hearts and good intentions, that we have clean hands and clear consciences and that this anti-racist stuff can be for someone else to do. Gerald (2020) terms this the “altruistic shield.” It is a dangerous complacency, and we need to work to disabuse ourselves and our peers of it.

My Terms for Curriculum

In this post I hope to provide some general orienting ideas as to where in the ESL curriculum we should consider bringing in anti-racism. By no means will this be comprehensive or authoritative, but this appears to be a gap in the literature and I hope this piece plays some role in closing that gap and giving rise to further work.

I’ve come to learn that even seasoned practitioners struggle with curriculum design. It’s big. It can feel abstract and distant from what happens in the classroom. It can feel more like an accountability measure than a tool. We seem even to lack a common language with which to discuss it: one person’s aim is another person’s objective is another person’s SLO. And the situation is exacerbated by the fact that so many places are simply doing curriculum badly. Most teachers, I’ve found, view curriculum as an annual chore that distracts from the actual meat of their work.

So when we consider the prospect of incorporating the difficult work of anti-racism into the chore of curriculum design, the task can seem daunting, to say the least. Because curriculum can be so daunting and its terms so slippery, I want to begin by briefly mapping my own terms and conception of curriculum.

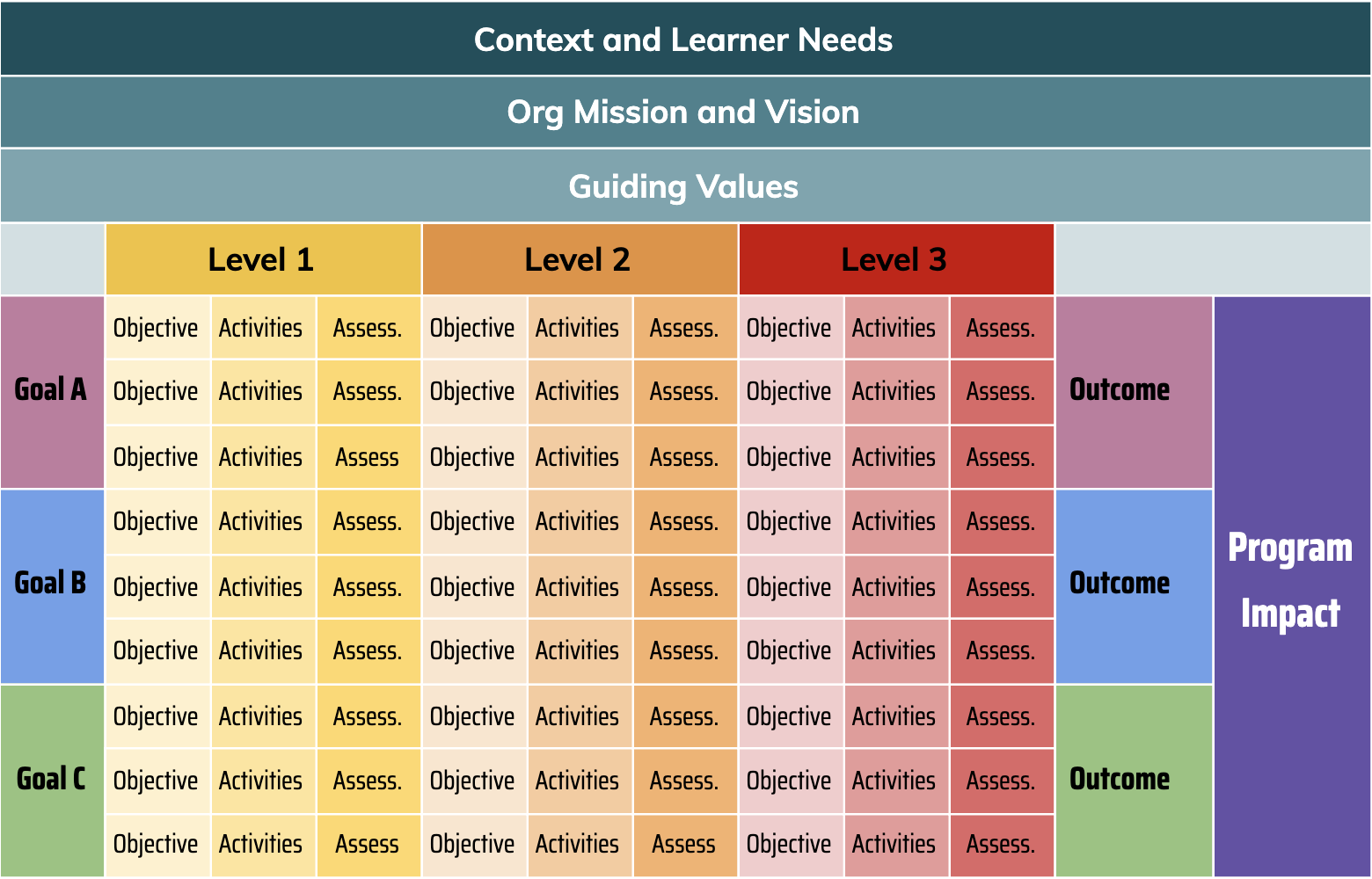

A well designed curriculum ought to be situated to the context and learner needs (all bolded terms in this section are illustrated in Table 1). Quite often, an ESL program is housed within a larger institution or organization, in which case that entity’s mission and vision become an important component of the context, to which the program’s guiding values ought to be aligned.

Within this context, a program can develop a handful of broad, program-spanning goals, such as:

Students will develop the written English skills needed to navigate daily life in the US.

Then, from goals, flow objectives—like goals but more specific, narrowly defined, and time-delimited. The relationship between well-written objectives and goals should be such that, by achieving all the constituent objectives, learners also achieve the goal. The objectives under the goal above might include:

Students will be able to complete everyday forms.

Flowing from those program-spanning goals on the left hand side are the program-spanning outcomes on the right hand side. A corresponding outcome might be:

89% of our 137 students demonstrated a meaningful improvement in the written English skills needed to navigate daily life in the US.

Strands are the single rows of aligned objectives progressing from left to right across levels, as shown in Table 2. They are narrower than goals and they develop by increments as students progress through a course or program. Here is an example strand focused on the ability to describe oneself and one’s needs for purposes such as completing forms. Another writing strand within this goal might focus on communicating with friends and neighbors via text and email.

So, with this framework in mind, where can anti-racism go?

Positions of Power

This isn’t, strictly speaking, curriculum, but the single most important place that we can locate anti-racism is in positions of power. Decision-makers at all levels in an organization or school—administrators, board members, executives, curriculum coordinators, teachers—should be diverse, representative of the community served, and committed to anti-racism. A roomful of monolingual white people making the decisions about an ESL program serving the immigrant community is a problem. Similarly problematic is a group of white people making decisions about what anti-racism is going to look like in the program. Yet this is all too often precisely what happens.

In practice, I understand that many of the folks reading this blog post will not be in a position to change the makeup of an organization’s leadership. What we can do is be sure to involve a range of stakeholders—teachers, students, community members, former students—in the curriculum development process at various points and in various modes. Form committees. Convene focus groups. Conduct surveys. Hire consultants. Listen, do so with a sincere desire to learn and change, and then do the work: learn and change.

Guiding Values

Within the curriculum proper, the highest level where we can locate anti-racism is in curricular values. Articulating the guiding values of a curriculum is an essential—yet woefully overlooked—early step in the curriculum design process. Wherever possible, values should be developed with ongoing participation from the community served.

Here are a few examples of guiding values from curriculum projects I recently worked on:

-

We agree to ensure that classrooms are inclusive and welcoming to all.

-

We agree that course content should reflect our students’ realities and goals.

-

We agree to make every effort to bring the classroom to the world and the world to the classroom.

To some, this might feel like a fluffy extra, something that can be skipped if time is tight, but racism perfectly exemplifies why it is imperative that we explicitly declare our guiding values at the outset.

Curriculum always and inevitably reflects values. Failure to declare those values does not mean our curriculum is neutral or free of values; it simply means the values will be inherited from the status quo. In ESL, that is a status quo that continues to erase, minimize, and sanitize the experiences of Black, queer, and poor people, to name only a few. This is one of the ways that white supremacy and structural racism replicate and permeate institutions, even those composed of well-meaning individuals who may not be personally bigoted.

So, within a status quo of pervasive structural racism, it is important to adopt explicitly anti-racist values in our curriculum design. Establishing such values is one of the first steps in a curriculum design process. Values should inform downstream curriculum decisions such as what content looks like, which materials are selected, what the recommended classroom activities are, and how outcomes are assessed. Values can be included in the front matter of curriculum documents, shared with new teachers and students, posted in classroom walls, and incorporated into brochures. They should also be used to hold us accountable, by empowering stakeholders to point to the stated values when the program is falling short of them.

Strands

Anti-racism could be incorporated as an explicit curricular strand. Strands of linguistic and communicative objectives are familiar to most ESL teachers, but in many contexts there are additional strands that get woven into the curriculum as well. For instance, an academic IEP might include strands on research, academic integrity, and citing external sources. A program for adults with limited formal education might include a strand on, say, financial literacy or digital literacy. Similarly, a strand of anti-racist objectives could be integrated into a course, and indeed would sit nicely among the intercultural strands that many programs integrate.

In the Content

As we likely know, second language curriculum is weird, as far as curricula go, in that it requires a content distinct from the objectives. The objectives are likely communicative, but achieving those objectives requires that we communicate about something. For instance, in a textbook on my desk right now, a unit objective is about giving directions and describing locations, but the reading content specifically focuses on the immigrant communities of Little Havana and Little Saigon in Miami. In the content of our ESL curriculum—the reading and listening texts that we engage with, the writing and speaking prompts we give our students—is another place we might locate anti-racism.

This could take the form of readings that overtly discuss racism, but—because racism is so pervasive—there are countless areas where we can indirectly include content that raises students’ awareness of the effects of racism. For instance, the workplace, healthcare, city geography, and the education system are common themes in ESL programs, and systemic racism pervades all of them. Too often, what is depicted in our ESL materials and content as “American” culture, “American” healthcare, and so on, is in fact a sanitized version of the middle class monocultural white experience in The U.S.

Concluding Thoughts

What I’ve shared here are some possible points of entry when it comes to building an anti-racist ESL curriculum. These points are surely not exhaustive. Readers might note that I haven’t specified anti-racist outcomes, content, or guiding values. I don’t have the expertise to do that right but I hope they provide some structure and inspiration for future work in this area.

If anyone reading this post does have that expertise and the inclination to get more specific in a follow up, I’ve been told that the NYS TESOL blog would be interested in running it.

Rob Sheppard is an English teacher and curriculum developer from Boston living in Philadelphia. He is assistant director for curriculum and instruction at Temple University Center for American Language and Culture (TCALC) and founder of Ginseng English. He serves on the boards of PennTESOL East (as sociopolitical concerns chair) and the Literacy Council of Norristown.

Further reading:

Canagarajah, A. S. (1999). Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford University Press. Chicago.

Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2019). Bringing race into second language acquisition. The Modern Language Journal, 103, 145-151.

Gerald, J. P. B. (2020). Combatting the altruistic shield in English language teaching. NYS TESOL Journal, 7(1), 22-25.

Ramjattan, V. A. (2019). Raciolinguistics and the aesthetic labourer. Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(5), 726-738.